The Magic of Reading

Alchemy will never occupy a seat at the same table of scientific study as other reputable, empirical Sciences, such as Chemistry or Biology. Relegated to the backwaters of pseudoscience for centuries, as a scientific study it was derided for some of its questionable scientific practices, most notably phrenology (determining personality traits from bumps on a human head) and the theory of humors (which proposed that bodily fluids were associated with earth, wind, air and fire and that these, in turn, affected our emotional balance). Yet, when we look beyond these cringe-worthy, medieval practices, the word ‘alchemy’ itself, conjures an almost wistful and romantic connotation.

There is an ongoing allure associated with alchemy. If we understand its core principle as the transformation of something worthless into something valuable (for example, turning lead into gold) then there is something magical underpinning this inexplicable branch of Science. It is perhaps for this reason that the transformative quality of alchemy has been so neatly compared to the equally transformative quality of reading by Elisabeth Gruner, Associate Professor of English, in her article ‘Why the ancient promise of alchemy is fulfilled in reading’ (The Conversation, 8 May 2019).

In her article, Gruner reminds us that the profile of alchemy, and alchemists, was actually given a huge boost by the appearance of Nicholas Flavel in J.K Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. He was the alchemist who created the philosopher’s stone, capable of turning lead into gold and developing the elixir of life. Not only does the practice of alchemy feature in a wide array of fantasy novels for young adults, the act of alchemy happens within the actual pages of most adolescent fiction – the promise of transformation “even if it requires great sacrifice”. The orphaned wizard, the oppressed teenage girl selected to fight to the death to save her family and community, a young Jewish girl who survives the Holocaust against terrible odds, the bullied teenager, the lonely teenager, the confused and marginalised teenager. What is so magical and empowering about these books is not that the main character magically transforms into something stronger or better; rather, that the stronger and heroic version of themselves emerge in the face of difficulties – the moment of magic is in the realisation that this stronger version of themselves was always there and is capable of great things.

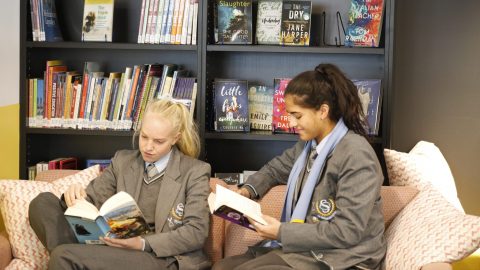

If we extend this metaphor even further, we can recognise the same transformative power of alchemy in the actual process of reading. When we read those words on the page, the circuits in our brains transform the different combinations of letters into images, sounds and ideas. In a pure act of alchemy, those pages are transformed into stories and we are, in turn, emotionally transformed. To not only immerse ourselves or, even better, lose ourselves in the world of the book, but to discover other worlds, other cultures, other ways of being. Perhaps we see a little of ourselves as well. In the libraries at St Catherine’s, we see this act of alchemy every day. Books from our shelves borrowed again and again, their pages turning to stories and transforming the minds of our readers.