Neuroarchitecture – A New Branch of Design

Architecture is the art and science of making sure our cities and buildings actually fit with the way we want to live our lives. – Bjarke Ingels, Danish Architect.

Architecture. Whether you notice it, appreciate it, love it or do not even really think about it, we can all agree that life would look very different without it. Architecture, the most public and therefore scrutinised of the Arts, is much more than a building. It dictates human movement, requires an understanding of anthropology and reflects the social values of our communities. The primary focus of this industry has shifted from sustainable practice to creating bespoke spaces that are people-centred, which is very much driven by neuroscience. Enter ‘Neuroarchitecture’ – a new branch of design that questions how environment affects cognition, assesses the plasticity of activity and strives to create multisensory space.

So, given that architects and neuroscientists are now talking, how can architecture as a field be taught in a classroom? Over the past 10 weeks, St Catherine’s Year 11 students have undertaken project-based learning to design a community centre – focussing first on the exterior and then considering the interior. One of the challenges of teaching a VCE study is tackling the immense amount of content and allowing adequate time for knowledge application. This project has permitted students to become far more invested in what they are designing, where skills have been intertwined into their project over time.

Students were presented with a brief to design a community centre. As a class, they began by brainstorming what they felt constituted a community space. From here, each student collected research through word associations – asking a range of people, ‘what is the first word you think of when I say home?’. These results were collated and analysed, which assisted in building a picture of target audience expectations. Visual imagery was added and physically connected to this research, which culminated in a class mood board. This foundation of investigatory work was consistently referred to throughout the project – encouraging ongoing conversation and reminding students to remain on track with their design choices.

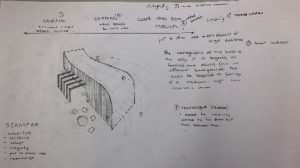

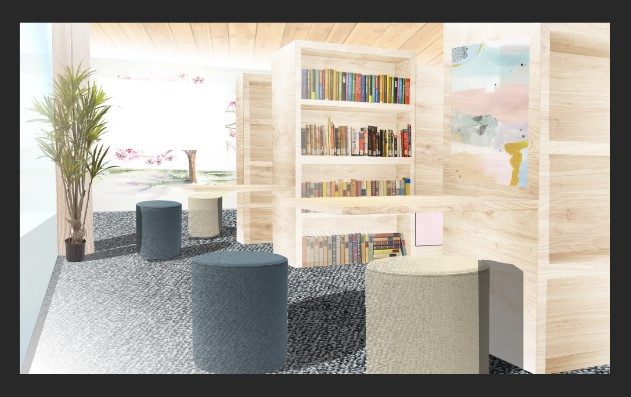

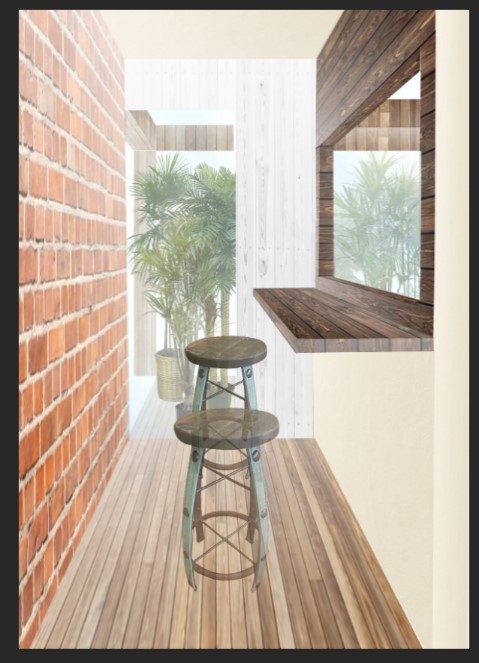

Once the ground work had been completed, it was now time to independently design. When tasked with designing a building, it is difficult to know where to begin. As well as creating an interesting and dynamic form, students needed to consider spatial configuration, interior organisation and the way people will enter, move through and engage with the space. We began the design process by using creative thinking strategies – a step-by-step framework that guides thinking. Although formulaic, it encourages students’ independent thinking without relying too much on the advice of the teacher. The first task was ‘white cube’ where students drew a perspective cube and applied a seven-step creative thinking strategy. This took roughly 45 minutes and by the end, everyone had a building to start with. Ongoing peer discussion and feedback directed the design process before students made final decisions about their work and polished presentations appropriate to the client.

Peer conversation and feedback – students were required to clearly communicate a positive aspect and something that required improvement.

What I observed throughout this project was that students had gained greater insight into and appreciation for architecture and interior design. Architecture influences the way we think, feel and live. Our designers of the future need to walk into the industry with the utmost respect for the impact architecture can have on communities and the people who live in them. This project started with a reading from Alain de Botton’s novel Architecture of Happiness and acts as a reminder of how buildings can incite powerful emotional responses:

After 10 minutes in the cathedral, a range of ideas that would have been inconceivable outside began to assume an air of reasonableness. Under the influence of the marble, the mosaics, the darkness and the incense, it seemed entirely probable that Jesus was the son of God…it was no longer surprising to think that an angel might at any moment choose to descend. Concepts that would have sounded demented 40 metres away in the company of vats of frying oil in the Westminster branch of McDonald’s, had succeeded – through a work of architecture.

-

Final student work: Lucy Motteram and Eliza Crossing.

-

Final student work: Lucy Motteram and Eliza Crossing.

-

Final student work: Lucy Motteram and Eliza Crossing.